Third article: Investment funds underperform chimpanzees

Why do people entrust their savings to an investment fund? Because they believe that professional managers are skilful. But the reality is quite different. These so-called financial geniuses don't know how to manage any better than the average person - they even perform worse than a chimpanzee!

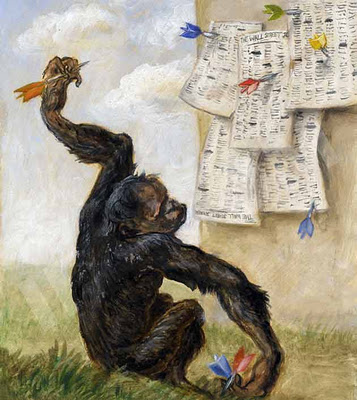

In 1993, the Swedish newspaper Expressen inflicted a monumental disgrace on stock market professionals. It organised a competition to see who could achieve the best performance on the stock market. Each participant received 10,000 kronor as a start-up prize. There were six contestants: five professional investors and a female chimpanzee named Ola. Ola was the winner. Between 3 August and 3 September 1993, her deposit increased by 1,542 kroner, significantly more than the portfolios of the humans. But the selection method used by the chimpanzee was a shaky one: throwing darts at a list of stocks quoted on the Stockholm stock exchange (30 March 2009, www.bernerzeitung.ch).

In 1993, the Swedish newspaper Expressen inflicted a monumental disgrace on stock market professionals. It organised a competition to see who could achieve the best performance on the stock market. Each participant received 10,000 kronor as a start-up prize. There were six contestants: five professional investors and a female chimpanzee named Ola. Ola was the winner. Between 3 August and 3 September 1993, her deposit increased by 1,542 kroner, significantly more than the portfolios of the humans. But the selection method used by the chimpanzee was a shaky one: throwing darts at a list of stocks quoted on the Stockholm stock exchange (30 March 2009, www.bernerzeitung.ch).

In January 2009, a challenge was launched in Moscow. The female Luscha, a red-faced macaque, had to choose 8 favourite stocks from 30 cubes representing major Russian companies. Her initial deposit of one million roubles tripled in the space of a year, leaving her human competitors, a host of experienced analysts with diplomas, far behind. "94% of all Russian funds underperformed the monkey", commented Oleg Anissimow, editor-in-chief of Finanz magazine (12 January 2010, www.aktuell.ru).

The American magazine Forbes introduced a "monkey portfolio" (Monkey Business). Its value increased by 70%, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) rose by only 15% in the same period. "Forbes, in 1967, put together a portfolio of 21 stocks selected by darts. 17 years later, the test was completed. The dart deposit exceeded the market average by 370% and was far superior to any portfolio manager" ("Amüsant: Fondsmanager vs. Affe", 7 March 2012, www.privataktionaer.de).

The American magazine Forbes introduced a "monkey portfolio" (Monkey Business). Its value increased by 70%, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) rose by only 15% in the same period. "Forbes, in 1967, put together a portfolio of 21 stocks selected by darts. 17 years later, the test was completed. The dart deposit exceeded the market average by 370% and was far superior to any portfolio manager" ("Amüsant: Fondsmanager vs. Affe", 7 March 2012, www.privataktionaer.de).

Let's classify the simian champions according to the length of their management: 1 month (chimpanzee), one year (macaque), 17 years (American monkey). Whether in the short, medium or long term, the investment fund is beaten to the punch by the animal.

Remember the countries: Sweden, Russia, United States. Whatever the geographical region, investment funds perform worse than monkeys.

And finally the periods: 1967 - 1984, 1993, 2009. Whatever the economic climate at the time, the investment fund is dumber than the beast.

So, whatever the possible scenario for your investment (duration, geographical area, current or future economic climate), if you want to invest in the stock market, it seems preferable to manage your hard-earned savings yourself. That way, you'll save on the management fees charged by the investment fund, and you can always make a donation to the zoo...

Why is it so bad to rely on highly qualified analysts?

Every bank or insurance employee is essentially a salesperson for products marketed by the institution that employs them, and by no means an independent and impartial advisor. Their career and the profitability of their agency depend on the number of people they lead to subscribe to their bank's or insurance company's investment funds. His title of "financial adviser" is a misnomer, because he is actually selling financial investments. According to a study by the University of Frankfurt am Main, based on data from a major German bank and a major online stock market service, customers who closely follow the recommendations of "financial advisers" boost the branch's profit by 20%. But this expense is totally unjustified, given that their deposit performs no better than the investments of customers who have not taken "advice" from the banker ("Der nutzlose Anlageberater", 30 May 2011, www.bernerzeitung.ch).

Every bank or insurance employee is essentially a salesperson for products marketed by the institution that employs them, and by no means an independent and impartial advisor. Their career and the profitability of their agency depend on the number of people they lead to subscribe to their bank's or insurance company's investment funds. His title of "financial adviser" is a misnomer, because he is actually selling financial investments. According to a study by the University of Frankfurt am Main, based on data from a major German bank and a major online stock market service, customers who closely follow the recommendations of "financial advisers" boost the branch's profit by 20%. But this expense is totally unjustified, given that their deposit performs no better than the investments of customers who have not taken "advice" from the banker ("Der nutzlose Anlageberater", 30 May 2011, www.bernerzeitung.ch).

An investment fund has considerable operating costs (salaries, office supplies, rent, etc.), and it is the subscriber who has to bear the burden of these "management costs" each year.

What's more, "financial advisers" and investment fund managers often tend to engage in intense buying and selling activity, in the name of active portfolio management, adapting to promising new opportunities, or eliminating previously acquired securities that are performing less well than expected. But each time a share is bought or sold, the investor has to pay brokerage fees. And in the case of investment fund units, there are entry or exit fees to pay each time.

What's more, every investment fund has its own very strict and rigid internal rules, which define its investment strategy. For example, if a fund targets Asian markets, the fund manager is required always to invest at least 80% of the total in Asian equities, never to buy commodities, never to have more than a certain percentage in cash, and so on. With a regulatory straitjacket like this, management is bound to be extremely inflexible. As a result, it is unable to anticipate the sometimes sudden variations in the market, and it is forbidden to seize certain opportunities that lie outside its predefined domain.

What's more, analysts all read the same information at the same time, and most react in the same way at the same time. One piece of good news about a major company, and the horde rushes in to buy the precious share that should rise, and does rise, precisely because everyone has the same buying reflex. Unfortunately, this fashion phenomenon means that people buy an overvalued asset, which has little future potential because it is already overpriced. The herd mentality of analysts leads them to buy overpriced stocks that are in vogue, whereas the monkey, using darts thrown at a list of listed stocks, chooses at random, and thus hits companies that nobody pays attention to, and which are therefore undervalued, and therefore offer great potential for capital gains in the future.

Walter Krämer, Professor of Economic Statistics at the University of Dortmund, explains that the stock exchange incorporates new information about companies into its quotations. "Generally speaking, this works very well. But there is one thing to consider: the enormous speed at which this happens. When an important piece of information is released, it is reflected on the stock market in the space of just a few seconds. "A few seconds after an important piece of information has been circulated, a share price is formed which, more or less, reasonably reflects this news. Then, in the wake of this development, an armada of so-called experts rises up, pretending that it could really be good for investors". But the exact opposite is true: the price movement has already taken place, and the advice of the so-called "experts", who predict that the upward/downward movement will continue, is exaggerated beyond measure, so that the naive people who put their trust in them are investing at a loss. "Any tip made public is worthless" ("Affe schlägt Börsenmakler", www.wirtschaftsmagazin-ruhr.de).

In 2013, a study by the prestigious Cass Business School (City University, London) proved that random selection not only beats active human management, but even passive management. The active manager selects a few stocks in particular, and hopes, with his 'basket' thus constituted, to beat the performance of all the stocks listed on the stock exchange, whereas the passive manager is content to bet on a set of stocks, called an 'index', for example the CAC40, the DAX, or the Dow Jones. Using computers that simulate the simian brain, Cass researchers constructed an almost infinite number of random investments (1,000 stocks taken at random to form an index; choice repeated ten million times, for each of the 43 years from 1968 to 2011, with geographical diversification across 13 stock markets).

In 2013, a study by the prestigious Cass Business School (City University, London) proved that random selection not only beats active human management, but even passive management. The active manager selects a few stocks in particular, and hopes, with his 'basket' thus constituted, to beat the performance of all the stocks listed on the stock exchange, whereas the passive manager is content to bet on a set of stocks, called an 'index', for example the CAC40, the DAX, or the Dow Jones. Using computers that simulate the simian brain, Cass researchers constructed an almost infinite number of random investments (1,000 stocks taken at random to form an index; choice repeated ten million times, for each of the 43 years from 1968 to 2011, with geographical diversification across 13 stock markets).

Andrew Clare, one of the lab's scientists, expressed his shock: "What shocked us most was that almost every one of the ten million monkeys managing an investment fund beat the performance of the real indices" ("Affen machen mehr Gewinne als Investoren, 18 April 2013, www.welt.de).

This staggering phenomenon can be explained as follows: most of the indices that actually exist are composed in such a way as to give great weight to large companies with a high stock market value, to the detriment of SMEs with a low market capitalisation. Such a weighting takes too much account of companies that have already succeeded and grown, and does not give enough importance to those that are still in a period of growth. As a result, the weighted index overlooks the promising developments of young companies with strong growth potential. This is why real indices, based on weighting according to market capitalisation, do not contribute as much to the success of growing SMEs as an index without weighting, compiled randomly by an orangutan or by a computer's random generator.

Watch out for dry losses!

There is a widespread scam known as a "Ponzi scheme", or "snowball", "pyramid" or "chain", in which investors' investments are remunerated by funds contributed by new entrants. The high returns promised attract new victims, who finance the interest paid to the previous investors, and the system grows like a snowball, until the pyramid is no longer able to attract enough new capital to cover the fees paid to clients.

This type of fraudulent financial arrangement takes its name from Charles Ponzi, who was active in Boston in the 1920s.

The first major scandal after the Second World War was that of the German fund Investors Overseas Services (IOS), which made happy profits for twelve years until the fraud was discovered and the company filed for bankruptcy in 1973. Around 250,000 German savers were affected, with cumulative losses of around 3.5 billion marks.

Around $65 billion evaporated in 2008 when one of Wall Street's leading investment funds, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, collapsed. Madoff had set up a Ponzi scheme and was sentenced to 150 years in prison.

Unfortunately, there are many other examples of fraudulent funds.

But losses are not always the result of criminal activity. Incompetent managers are more than enough to ruin you! The following are several funds that have caused losses, even though each specialises in a completely different field! Each of these funds has been/is a disaster, whatever the specific area of expertise.

Bond funds: In 1994, the Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) fund was set up by top mathematicians. Among its directors were academics Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1997 for having devised a formula for calculating derivative options. Armed with sophisticated mathematical models and using complex software, the group embarked on interest rate arbitrage, initially with success. But in 1998, the reality of the world turned out to be different from the forecasts calculated in the laboratory, so that in a few days the fund lost all its capital. As the fund had taken bets worth 1,200 billion dollars, and its collapse would have destroyed the international banking system, it had to be saved at the last minute by a massive injection of new capital, and its positions gradually unwound.

Equity fund : The "Sarasin Equisar Global" investment fund (ISIN: LU0088812606) "invests globally in equities in markets and sectors that promise the best overall returns over the long term" (www.sarasin.ch). What are we to make of this tempting prospectus promise? The fund was created in 1998 by Swiss private bank Sarasin, which has been in existence since 1841. This reputable bank's centuries of experience should spare it the mistakes of a beginner. However, this was not the case, as the bank fell flat on its face during the 2008 crisis. Sarasin Equisar Global did not anticipate the stock market plunge in 2008! But then, if a bank that is almost two centuries old is incapable of anticipating a downturn and allows itself to be taken by surprise like any totally inexperienced illiterate person, what is the point of its investment fund? What's the point of paying management fees for a non-existent service?

Equity fund : The "Sarasin Equisar Global" investment fund (ISIN: LU0088812606) "invests globally in equities in markets and sectors that promise the best overall returns over the long term" (www.sarasin.ch). What are we to make of this tempting prospectus promise? The fund was created in 1998 by Swiss private bank Sarasin, which has been in existence since 1841. This reputable bank's centuries of experience should spare it the mistakes of a beginner. However, this was not the case, as the bank fell flat on its face during the 2008 crisis. Sarasin Equisar Global did not anticipate the stock market plunge in 2008! But then, if a bank that is almost two centuries old is incapable of anticipating a downturn and allows itself to be taken by surprise like any totally inexperienced illiterate person, what is the point of its investment fund? What's the point of paying management fees for a non-existent service?

Precious metals fund: The Tell Gold & Silber Fonds investment fund (ISIN: LI0023785673) has set itself the goal of outperforming the physical metal, using leverage such as options on derivatives or mining shares (www.tellgold.li). Given the favourable economic climate (bull market), the favourable environment (located in the tax haven of Liechtenstein) and the team of experts, we should have expected a stellar performance. However, from its inception to date (7 January 2007 - 10 May 2013), it has lost 88% of its value, while the underlying asset has doubled in the same period (gold +100%, silver +100%). It could hardly be worse: while the value of the underlying asset has doubled, over the same period the fund has been ruined by the 'experts' who manage it!

Precious metals fund: The Tell Gold & Silber Fonds investment fund (ISIN: LI0023785673) has set itself the goal of outperforming the physical metal, using leverage such as options on derivatives or mining shares (www.tellgold.li). Given the favourable economic climate (bull market), the favourable environment (located in the tax haven of Liechtenstein) and the team of experts, we should have expected a stellar performance. However, from its inception to date (7 January 2007 - 10 May 2013), it has lost 88% of its value, while the underlying asset has doubled in the same period (gold +100%, silver +100%). It could hardly be worse: while the value of the underlying asset has doubled, over the same period the fund has been ruined by the 'experts' who manage it!

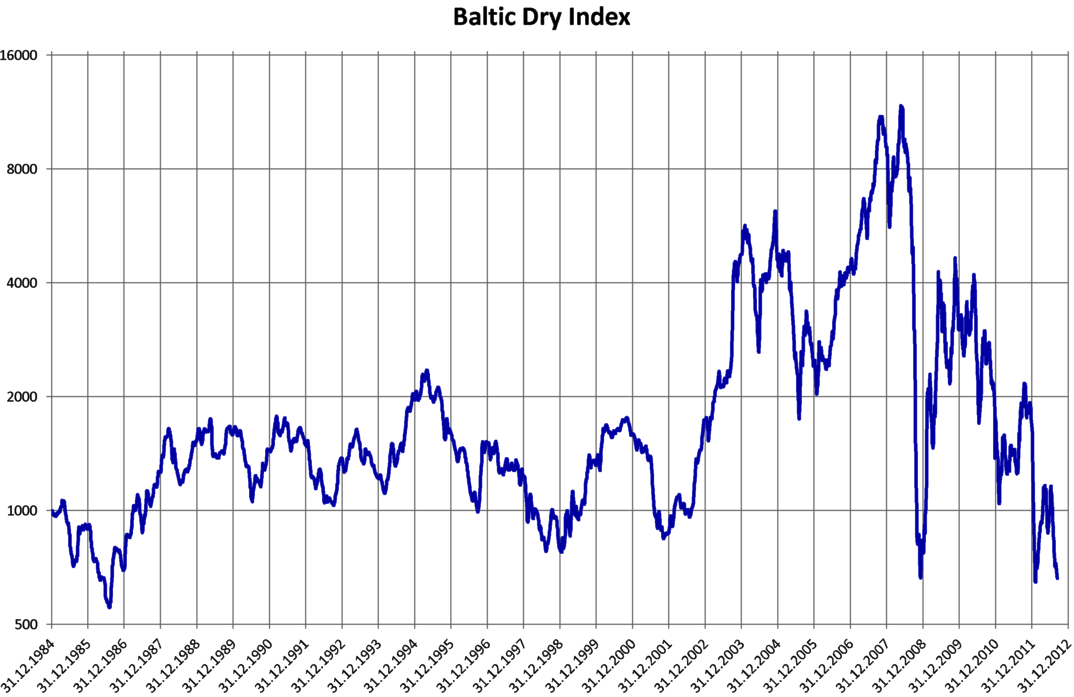

Ship's bottom: Globalisation is leading to an increase in the volume of international trade. Since most imports and exports are transported by sea, the increased demand will push up freight rates, and therefore the profits of shipping companies and shipowners. So the best thing to do would be to invest in the acquisition of cargo ships, wouldn't you agree? Fascinated by this reasoning, many wealthy people subscribed to funds to build one or more ships. However, they should have paid attention to the small print in the issue prospectus: if the company is undercapitalised, subscribers are obliged to add funds! And so it was that, when transport prices collapsed in 2008, many savers were unpleasantly surprised to learn that their fund was taking on water and that they were being asked to bail it out. Given that, after the artificial recovery of 2009 - 2010, the recession is starting again, and freight costs are falling again, it's a safe bet that their woes aren't over yet!

Opposite, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), a price index for bulk maritime transport. Although it took off spectacularly from 2000 onwards, it collapsed even more spectacularly during the economic crisis of 2008. After a modest rebound in 2009, it plummeted steadily until 2013, as the economic situation continued to worsen.

Opposite, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), a price index for bulk maritime transport. Although it took off spectacularly from 2000 onwards, it collapsed even more spectacularly during the economic crisis of 2008. After a modest rebound in 2009, it plummeted steadily until 2013, as the economic situation continued to worsen.

Film industry funds: German tax legislation exempts investments in the film industry from tax. This has led to investment funds producing films. But not only were most of these films flops, resulting in negative returns, but the Ministry of Finance cancelled the tax advantage in 2010 with retroactive effect back to 1998, on the grounds that the investors' real aim was tax optimisation, not the production of feature films! Between 1998 and 2005, 70,000 savers had invested in such funds, in the hope of saving tax, and now their recovery amounts to 2.5 billion euros.

Sprawling funds: Austrian ex-billionaire Christian Baha is the founder of "Superfund", a sprawling institution that has launched around twenty investment funds on the market. The operating costs, which are borne by investors, are exorbitant: 6% of the amount subscribed each year, plus 25% of the gains. After initial successes, 21 of the 22 funds are now in the red. But Baha continues to charge its management fees unperturbed ("Christian Baha, ein Star stürzt ab", 8 May 2012, www.format.at).

Conclusion

The sad case studies mentioned above show that investment funds should be avoided in every conceivable scenario, i.e. whatever the :

- duration (short, medium or long term),

- geographical area

- economic conditions,

- management (active or passive),

- specialisation (bonds, equities, precious metals, boats, films or multi-support).

The managers of Sarasin Equisar Global were unable to anticipate the collapse of the stock market in 2008, so why pay management fees to blind people?

The LTCM was wrecked, even though it was run by top-flight mathematicians, including two Nobel Prize winners in economics. Or, to put it more accurately, you shouldn't say 'even though', but 'because'. Because this investment fund was ruined precisely because it was run by Nobel Prize winners with mathematical fantasies that ran counter to reality! We would certainly have limited the damage if we had entrusted the management of the LTCM to a monkey.

It really is more profitable and less risky to entrust the investment of your savings to a monkey than to self-proclaimed "experts"! So-called professional experts always impress the crowds. But when their pitiful counter-performances, not to say their antics, are laid bare, shouldn't we conclude that it's better to manage your own destiny, without relying on the punctured pipes of the stock market traders, without adding credence to the mirific prospects of the swindlers, without being swindled by the financial advisers who sell smoke and mirrors?

Author : Euporos SA

Source : www.euporos.ch

Comments

No current comments